The History

Where the Road Began

In the early 1800s, there were no maps of the country between Sydney and Newcastle. To find a way through, explorers had to go out in the country, usually with Aboriginal guides, to search for routes along which it would be possible to build a road. This was often a difficult and rugged experience and many returned home, battered and exhausted without finding a way. In spite of their difficulties, some made it through and you can see extracts from their diaries in this section. The reward for the explorer was usually a grant of land, which meant wealth and prestige to them, so there was plenty of motivation for them to try.

A number of explorers came back with ideas for an official road north, each route or “line” called by the name of the person who suggested it. Often these routes were existing Aboriginal pathways shown to them by their guides.

A number of explorers came back with ideas for an official road north, each route or “line” called by the name of the person who suggested it. Often these routes were existing Aboriginal pathways shown to them by their guides.

The 1820s

By the early 1820s the Colony was expanding rapidly and settlers began taking up land in the fertile Hunter Valley. Sailing ships were the only way people, goods and stock could get to and from Sydney. The settlers petitioned for a decent road. In 1825 Assistant Surveyor Heneage Finch was sent to survey a suitable route. He followed a number of aboriginal tracks along the ridge-tops.

Governor Ralph Darling immediately assigned convict road gangs to start building the road. Rather than be allowed to languish in gaol, many convicts who had committed another offence were sent to build roads in remote areas. They were assigned to Iron Gangs and worked in leg-irons – an iron collar around each ankle was joined together by a length of chain. Weighing up to 6 kg these could only be put on or removed by a blacksmith. After completing a sentence in an Iron Gang men were often transferred to a Road Party, where they undertook the same work, but without having to wear leg-irons.

One overseer was assigned to each gang of between 50 and 60 men. The Surveyor General appointed one of his principal surveyors – called Assistant Surveyors – to supervise construction in each area, with several convict gangs to undertake the work. The men lived and worked under difficult conditions – the discipline was harsh and the shelter minimal. Permanent camps with timber or bark huts were built where the men were likely to be stationed in the one area for a long while, but in other places men lived in tents which could be moved as the road progressed. Some convicts absconded, but most didn’t stay at liberty for long as the bush was wild and forbidding to those unaccustomed to it.

Governor Ralph Darling immediately assigned convict road gangs to start building the road. Rather than be allowed to languish in gaol, many convicts who had committed another offence were sent to build roads in remote areas. They were assigned to Iron Gangs and worked in leg-irons – an iron collar around each ankle was joined together by a length of chain. Weighing up to 6 kg these could only be put on or removed by a blacksmith. After completing a sentence in an Iron Gang men were often transferred to a Road Party, where they undertook the same work, but without having to wear leg-irons.

One overseer was assigned to each gang of between 50 and 60 men. The Surveyor General appointed one of his principal surveyors – called Assistant Surveyors – to supervise construction in each area, with several convict gangs to undertake the work. The men lived and worked under difficult conditions – the discipline was harsh and the shelter minimal. Permanent camps with timber or bark huts were built where the men were likely to be stationed in the one area for a long while, but in other places men lived in tents which could be moved as the road progressed. Some convicts absconded, but most didn’t stay at liberty for long as the bush was wild and forbidding to those unaccustomed to it.

Engineering a Road

The engineering techniques used to build the road were at the cutting edge of technology at the time, incorporating the latest European ideas. The work was labour-intensive and the equipment crude. Up to 700 convicts worked on the Road at any one time – clearing timber, digging drains, blasting and shaping stone, and shifting it into position. Some of the blocks weighed up to 660 kg. Originally 33 bridges were built, their timber decks often supported by elaborate stone foundations. The few which remain are the oldest bridges in mainland Australia.

Where the Road followed the top of the ridges, the construction mostly involved clearing a path about 20 metres wide, grubbing out the stumps from the centre and creating a level surface. The convict labourers did not require any special skills to undertake these tasks. However some sections of the construction required highly skilled stonemasonry. Stone walls were needed to support the road where it climbed steeply up or down hillsides, through steep gullies or across watercourses. A wall on Devines Hill just north of Wisemans Ferry reaches almost 10 metres, and was supported by 5 massive buttresses.

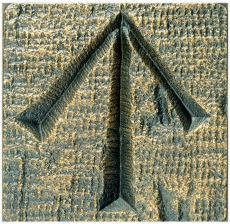

Sandstone was quarried from near the Road, using jumper bars and gunpowder. The stone was then cut to shape and placed in position, forming fine masonry walls of squared stones. No mortar was used to hold the stones together.

Cleverly designed drainage systems kept rainwater from the surface of the Road. Drains were cut along the high side of the Road, and the water diverted into stone-lined culverts under the road, to flow away where it would not damage the structure.

The Road surface was formed by placing larger stones as a foundation layer, with layers of progressively smaller stones on top, and the surface was finished with a smooth layer of small, gravel-like stones. Where the road continues to carry modern traffic much of the surface is now tar sealed.

Much of the high quality construction was carried out under the supervision of Assistant Surveyor Percy Simpson, based at Wisemans Ferry between 1828 and 1832, and Heneage Finch, who was in charge of construction around Bucketty and Laguna in 1830-31.

Simpson was an engineer who had a sound knowledge of the latest road construction techniques being developed in Europe. He had the most difficult sections to build, like the steep descents from the ridgeline to the Hawkesbury River at Wisemans Ferry. Much of the high quality work done under his command remains intact today – a tribute to his ability to lead an unskilled and unwilling labour force to produce such an engineering masterpiece.

Not all sections of the Road were constructed to the same standard, the quality of work depending on the skills of the men in the gangs, their overseer, and the Assistant Surveyor in charge.

In 1832 the first steamships began replacing sailing ships, so sea travel became safer and faster. By 1833 the road was almost complete. However sections of the Road which passed along remote and desolate ridges, with little food or water for travelling stock, were not popular. Travellers quickly found it preferable to use alternative tracks, such as the one through the Macdonald Valley, where there were people and inns as well as fodder and water for stock. Fifty years later railways were opened, further reducing the traffic on the Road. In 1930, when motor cars were becoming a more popular method of travel, the Pacific Highway was opened. So the Great North Road became a quiet back road, where travellers can still experience the 19th century ambiance of its heyday.

Where the Road followed the top of the ridges, the construction mostly involved clearing a path about 20 metres wide, grubbing out the stumps from the centre and creating a level surface. The convict labourers did not require any special skills to undertake these tasks. However some sections of the construction required highly skilled stonemasonry. Stone walls were needed to support the road where it climbed steeply up or down hillsides, through steep gullies or across watercourses. A wall on Devines Hill just north of Wisemans Ferry reaches almost 10 metres, and was supported by 5 massive buttresses.

Sandstone was quarried from near the Road, using jumper bars and gunpowder. The stone was then cut to shape and placed in position, forming fine masonry walls of squared stones. No mortar was used to hold the stones together.

Cleverly designed drainage systems kept rainwater from the surface of the Road. Drains were cut along the high side of the Road, and the water diverted into stone-lined culverts under the road, to flow away where it would not damage the structure.

The Road surface was formed by placing larger stones as a foundation layer, with layers of progressively smaller stones on top, and the surface was finished with a smooth layer of small, gravel-like stones. Where the road continues to carry modern traffic much of the surface is now tar sealed.

Much of the high quality construction was carried out under the supervision of Assistant Surveyor Percy Simpson, based at Wisemans Ferry between 1828 and 1832, and Heneage Finch, who was in charge of construction around Bucketty and Laguna in 1830-31.

Simpson was an engineer who had a sound knowledge of the latest road construction techniques being developed in Europe. He had the most difficult sections to build, like the steep descents from the ridgeline to the Hawkesbury River at Wisemans Ferry. Much of the high quality work done under his command remains intact today – a tribute to his ability to lead an unskilled and unwilling labour force to produce such an engineering masterpiece.

Not all sections of the Road were constructed to the same standard, the quality of work depending on the skills of the men in the gangs, their overseer, and the Assistant Surveyor in charge.

In 1832 the first steamships began replacing sailing ships, so sea travel became safer and faster. By 1833 the road was almost complete. However sections of the Road which passed along remote and desolate ridges, with little food or water for travelling stock, were not popular. Travellers quickly found it preferable to use alternative tracks, such as the one through the Macdonald Valley, where there were people and inns as well as fodder and water for stock. Fifty years later railways were opened, further reducing the traffic on the Road. In 1930, when motor cars were becoming a more popular method of travel, the Pacific Highway was opened. So the Great North Road became a quiet back road, where travellers can still experience the 19th century ambiance of its heyday.