The Grand Vision

Government officials wanted the road to be a monument to their own importance, a road as good as any in England. The idea was that it would show everyone back in England that the colony was strong and successful and capable of doing as well as England did. More than that, it was designed to show off the capabilities of the individual Governors and decision-makers who built it.

“At the time the road was built, Sir Thomas Mitchell was Surveyor General. He had taken over in 1827, when John Oxley had died suddenly. To demonstrate that his own style of road building was better than the Oxley version, he tried to make sure that all roads were as straight as possible, within the limits imposed by the shape of the countryside, and that they branched in symmetrical and regular fashion, providing the most economical distances from place to place. Roundabout or curly roads were definitely not acceptable unless they could not possibly be avoided, even if the straight ones did not go exactly where people were living at the time! Sir Thomas Mitchell was criticised for trying to make this road into a monument to his own glory.”

Baron Charles von Hugel, travelling in Australia in 1834, summarised the feeling that many shared about the Surveyor General:- “This road was designed by Major Mitchell and executed by Mr Simpson. But, however flattering to his vanity this project may be, and however great a tribute to his skill and knowledge, it nevertheless reflects badly on his character, for certain sections of a few miles … have been deliberately left unfinished, making all the improvements brought about by the great expenditure on this pass useless [he was describing Devine’s Hill], for these other sections are almost impassable. They have been left like that purely to point up the difference between the former road administration and the present administration…. Up to the present, every Surveyor General has concerned himself with new routes which he has never had time to complete, and which his successor has either abandoned entirely or done nothing to improve, simply initiating something else which would bear his own name.”

“At the time the road was built, Sir Thomas Mitchell was Surveyor General. He had taken over in 1827, when John Oxley had died suddenly. To demonstrate that his own style of road building was better than the Oxley version, he tried to make sure that all roads were as straight as possible, within the limits imposed by the shape of the countryside, and that they branched in symmetrical and regular fashion, providing the most economical distances from place to place. Roundabout or curly roads were definitely not acceptable unless they could not possibly be avoided, even if the straight ones did not go exactly where people were living at the time! Sir Thomas Mitchell was criticised for trying to make this road into a monument to his own glory.”

Baron Charles von Hugel, travelling in Australia in 1834, summarised the feeling that many shared about the Surveyor General:- “This road was designed by Major Mitchell and executed by Mr Simpson. But, however flattering to his vanity this project may be, and however great a tribute to his skill and knowledge, it nevertheless reflects badly on his character, for certain sections of a few miles … have been deliberately left unfinished, making all the improvements brought about by the great expenditure on this pass useless [he was describing Devine’s Hill], for these other sections are almost impassable. They have been left like that purely to point up the difference between the former road administration and the present administration…. Up to the present, every Surveyor General has concerned himself with new routes which he has never had time to complete, and which his successor has either abandoned entirely or done nothing to improve, simply initiating something else which would bear his own name.”

Debate on the Route Continues

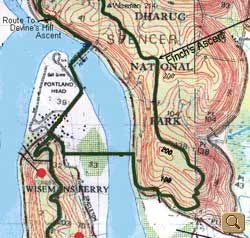

In spite of local objections, the route as far as the Hawkesbury River starting from Sydney was set by Mitchell. This new route cut off about four miles from the old road via Windsor and used Wiseman’s Ferry to reach the north side of the River where the road initially went up a steep spur onto the range that Heneage Finch had surveyed in 1825. There did not appear to be many options for ascending this steep spur.

Finch Ascent and Devines Hill

In 1827, John Dunmore Lang described travelling up this section of the road [Finch Ascent] while it was in the early stages of construction. While the view was beautiful, he does not appear to have been impressed by the road itself:- “The first rays of the rising sun were just beginning to gild the summits of the lofty ridges on either bank of the Hawkesbury, when we led our horses on the following morning towards the river, which we crossed in a punt or ferry boat constructed for the conveyance of men and cattle. The road on the opposite bank is still more precipitous and required greater labour for its construction; numerous convicts were at work on it as we climbed the mountain.” (Mitchell Library 2 vols, 991/27 A1 & A2)

Jonathon Warner was in charge of the building at this stage and was very pleased with the way it was going. He wrote to his boss, Captain William Dumaresq, to tell him so:- “Wiseman’s April 28th 1828 …I have now a party of No 8 Gang building Huts about eight miles on the Road, on the North side the River and shall have the whole of that gang across the water in about ten days – by the latter end of this week I shall be able to take a cart up the Hill on the North side of the river as far as where you come on top when you observe Wiseman’s farm. The road up by the Pailing on Roses ground is a very gentle ascent to the first turning where you went up with me and scarcely looks like going up a hill now it is made 4 yds wide, the part near the Pailing fence that looked a very steep side of a hill is an excellent road, and the highest wall not more than four feet – as I have kept in by the winding of the Hill to avoid all high wall building in future as much as possible.” (NSW Archives Office Box 4/2011.1)

However, not everyone shared his enthusiasm. In 1828, Governor Darling was visiting the roadworks and was horrified at the steepness of the road. He was quite sure that no vehicle would ever be able to get up it, so he ordered work to stop immediately and a new way up found. Everyone was aghast and Thomas Mitchell hurried to find another way up. The only alternative he could find was a steep pass beside Molly Devine’s property but this was going to need massive stone works before it could be used. Nevertheless, Devine’s Hill was confirmed as the new route and work began as soon as possible. The old road became known as the Finch Ascent or the 1828 road and can still be seen half-built today, as though workmen have just downed tools for a tea break. Click on the map image to go to a larger version of it.

Jonathon Warner was in charge of the building at this stage and was very pleased with the way it was going. He wrote to his boss, Captain William Dumaresq, to tell him so:- “Wiseman’s April 28th 1828 …I have now a party of No 8 Gang building Huts about eight miles on the Road, on the North side the River and shall have the whole of that gang across the water in about ten days – by the latter end of this week I shall be able to take a cart up the Hill on the North side of the river as far as where you come on top when you observe Wiseman’s farm. The road up by the Pailing on Roses ground is a very gentle ascent to the first turning where you went up with me and scarcely looks like going up a hill now it is made 4 yds wide, the part near the Pailing fence that looked a very steep side of a hill is an excellent road, and the highest wall not more than four feet – as I have kept in by the winding of the Hill to avoid all high wall building in future as much as possible.” (NSW Archives Office Box 4/2011.1)

However, not everyone shared his enthusiasm. In 1828, Governor Darling was visiting the roadworks and was horrified at the steepness of the road. He was quite sure that no vehicle would ever be able to get up it, so he ordered work to stop immediately and a new way up found. Everyone was aghast and Thomas Mitchell hurried to find another way up. The only alternative he could find was a steep pass beside Molly Devine’s property but this was going to need massive stone works before it could be used. Nevertheless, Devine’s Hill was confirmed as the new route and work began as soon as possible. The old road became known as the Finch Ascent or the 1828 road and can still be seen half-built today, as though workmen have just downed tools for a tea break. Click on the map image to go to a larger version of it.

Later on, in 1834, after much construction work had been done, Baron Charles von Hugel stayed with Solomon Wiseman on a journey from Newcastle to Sydney along the road. He commented on the steepness of the road:- “Wiseman invited me to stay several days with him, and to make a boat trip with him to visit the old road on the other side of the water, which was truly remarkable from the point of view of seeing what was expected of the horses.”

Once at the top of the hill, the road wound along a dry but easy ridge to Twelve Mile Hollow, the first place with any water since Wiseman’s. Twelve Mile Hollow originally got this name because it was twelve miles from Wiseman’s Ferry. When the Devine’s Hill route was developed, this shortened the distance to Ten Miles. Major Mitchell initially tried to solve the problem by calling the place after his friend, Colonel Snodgrass. For a while, it became Snodgrass Valley. However, many people still called it Twelve Mile Hollow, so eventually he decided to call it Ten Mile Hollow, to be more accurate, a name it still has today.

Mitchell wrote on the subject in his report to the Colonial Secretary on 8 October 1829:- “… as the new ascent at Wiseman’s shortens the distance two miles: and I have endeavoured to correct the error of the present name by substituting in the place thereof, that of Snodgrass Valley. The soil here seeming very good, it is also reserved for a village.” (Mitchell Library, CY 887 pp 258-260; Cy pos 916 ppLO 80-90)

The area of Snodgrass Valley was surveyed for a village and in August 1836 notice was given in the Gazette that lots were available for purchase at £2 each and could be seen on the plan at the Surveyor General’s Office in Sydney. However, the village did not develop and few lots were ever sold.

Once at the top of the hill, the road wound along a dry but easy ridge to Twelve Mile Hollow, the first place with any water since Wiseman’s. Twelve Mile Hollow originally got this name because it was twelve miles from Wiseman’s Ferry. When the Devine’s Hill route was developed, this shortened the distance to Ten Miles. Major Mitchell initially tried to solve the problem by calling the place after his friend, Colonel Snodgrass. For a while, it became Snodgrass Valley. However, many people still called it Twelve Mile Hollow, so eventually he decided to call it Ten Mile Hollow, to be more accurate, a name it still has today.

Mitchell wrote on the subject in his report to the Colonial Secretary on 8 October 1829:- “… as the new ascent at Wiseman’s shortens the distance two miles: and I have endeavoured to correct the error of the present name by substituting in the place thereof, that of Snodgrass Valley. The soil here seeming very good, it is also reserved for a village.” (Mitchell Library, CY 887 pp 258-260; Cy pos 916 ppLO 80-90)

The area of Snodgrass Valley was surveyed for a village and in August 1836 notice was given in the Gazette that lots were available for purchase at £2 each and could be seen on the plan at the Surveyor General’s Office in Sydney. However, the village did not develop and few lots were ever sold.

Why not the Finch Ascent?

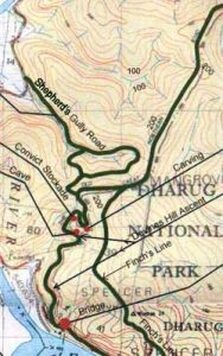

It was clearly evident to Governor Darling that the road for the ascent which had been put into effect by Lt. Jonathon Warner would be difficult for carts – and of course carriages – to be pulled up the slope of the road and that they would have extreme difficulty getting round the corners. It is interesting to look at a map, showing the ascent path and having contours on it.

The access to the ascent road runs downstream for a short distance (about a half km) on the north side of the Hawkesbury River. It is only about 20 to 30 metres above water level when it moves up the slope to the north. As Warner remarked, in his report to Dumaresq, he had kept in close to the winding of the hill to avoid building high retaining walls. The slope was gentle for this first part of the route. However, on inspection of the map about a half km from the river crossing, there is a bend to the north up a slope from the 20 metre contour, rising quickly through three sharp bends to loop around the 200 metre contour within about 300 to 400 metres of the roadway. The road which Warner had built was only “4 yards wide” (less than 4 metres). The gradient of the road must have been around 1 in 4 or steeper in places. No doubt Darling would have had recollections of some of the steep roads in England such as Porlock Hill rising up on to Exmoor in Somerset. It is a winding road with a long slope of 1 in 4. Even with a wide road, this would have been difficult for a horse and cart and more so for a carriage.

Convict Trail Project 2017We can look at a map which continues the Finch Ascent map above on the western side to see what Thomas Mitchell, assisted by Heneage Finch, had determined would allow the design of an acceptable road. There was a need to build a bridge over a stream running down into the River and that still exists. Mitchell realised that the road was to be built on the side of a steep slope which dropped down to a stream in a gully. There would have to be structural retaining walls and rock cut out from the eastern side of the hill. The extent of these structures will be discussed in the section on construction of the road on the Devine’s Hill Ascent. The map gives an indication of the considerable flow of water which must be expected to run off the sandstone ridges down into the gullies. With careful consideration of the best route around the highly sloping ridges, it looked to be possible to achieve gradients which would be no more than about 1 in 8 up the Devine’s Hill Ascent but generally thereafter the gradients would be much more gentle. This was the task which would be left to Lt. Percy Simpson who replaced Lt. Jonathon Warner. The roadway, rather than being only 4 yards wide, would finally be constructed to a width of around half to one chain wide (11 to 22 yards).

The access to the ascent road runs downstream for a short distance (about a half km) on the north side of the Hawkesbury River. It is only about 20 to 30 metres above water level when it moves up the slope to the north. As Warner remarked, in his report to Dumaresq, he had kept in close to the winding of the hill to avoid building high retaining walls. The slope was gentle for this first part of the route. However, on inspection of the map about a half km from the river crossing, there is a bend to the north up a slope from the 20 metre contour, rising quickly through three sharp bends to loop around the 200 metre contour within about 300 to 400 metres of the roadway. The road which Warner had built was only “4 yards wide” (less than 4 metres). The gradient of the road must have been around 1 in 4 or steeper in places. No doubt Darling would have had recollections of some of the steep roads in England such as Porlock Hill rising up on to Exmoor in Somerset. It is a winding road with a long slope of 1 in 4. Even with a wide road, this would have been difficult for a horse and cart and more so for a carriage.

Convict Trail Project 2017We can look at a map which continues the Finch Ascent map above on the western side to see what Thomas Mitchell, assisted by Heneage Finch, had determined would allow the design of an acceptable road. There was a need to build a bridge over a stream running down into the River and that still exists. Mitchell realised that the road was to be built on the side of a steep slope which dropped down to a stream in a gully. There would have to be structural retaining walls and rock cut out from the eastern side of the hill. The extent of these structures will be discussed in the section on construction of the road on the Devine’s Hill Ascent. The map gives an indication of the considerable flow of water which must be expected to run off the sandstone ridges down into the gullies. With careful consideration of the best route around the highly sloping ridges, it looked to be possible to achieve gradients which would be no more than about 1 in 8 up the Devine’s Hill Ascent but generally thereafter the gradients would be much more gentle. This was the task which would be left to Lt. Percy Simpson who replaced Lt. Jonathon Warner. The roadway, rather than being only 4 yards wide, would finally be constructed to a width of around half to one chain wide (11 to 22 yards).