Quarrying, Walls and Fills

Quarrying for the Great North Road

A row of wedge

pit marks.

A row of wedge

pit marks.

An important part of the Great North Road operations was the quarrying of the useful sandstone rock and the shaping of blocks for the construction of the many side walls and embankments which were necessary. Between Wiseman’s Ferry and Mount Manning, several large quarries have been investigated by Great North Road historians. Within the quarries, there are terraced levels where rock has been split. In some places, clear indications of the wedging methods which were used to extract the rock in suitable size pieces for conversion to prepared blocks. Large sections of rock were also moved from the face of the quarry by drilling and blasting, for further preparation into blocks.

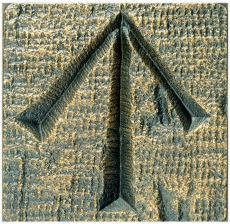

Conservation work in the largest of the quarries on Devine’s Hill above the buttressed wall revealed some interesting features and at least one of the pieces of equipment which the convicts had used. Wedge pits were dug into the rock about 10 inches (250mm) apart, using the pointed end of a pick, along a line suited to cracking of the block from the quarry face. Iron wedges were inserted in the pits so prepared, often with a piece of bark on each side of the wedge to aid the operation. The wedges were struck with a sledge hammer, working back and forth along the line of wedges until the rock cracked along the line. In a large quarry such as that at Devine’s Hill, it would often be necessary to assist in the cracking of a block of suitable dimensions, by using wedges inserted across the vertical face of the rock along a horizontal line. The action of a vertical and a horizontal crack would assist the quarryman to produce workable blocks

A row of wedge pits can still be seen in rock at the Devine’s Hill quarry. The rock had wedge pits along the horizontal face and along the vertical face as well. The block so cracked was left and it is not obvious why it was not used. During the conservation work in 1985, a small iron wedge was discovered. Ian Webb (Ref.1) notes that the wedge was 90mm by 40mm. A blacksmith had forged it by folding a strip of 40mm by 10-12mm bar in half. The folded end was forged and flattened to make the taper of the 40 mm wide wedge. Elsewhere, tools such as the head of a stone breaking sledge hammer, a pointed pick head and an iron stone chisel have been found (Ralph Hawkins, Ref.2).

Conservation work in the largest of the quarries on Devine’s Hill above the buttressed wall revealed some interesting features and at least one of the pieces of equipment which the convicts had used. Wedge pits were dug into the rock about 10 inches (250mm) apart, using the pointed end of a pick, along a line suited to cracking of the block from the quarry face. Iron wedges were inserted in the pits so prepared, often with a piece of bark on each side of the wedge to aid the operation. The wedges were struck with a sledge hammer, working back and forth along the line of wedges until the rock cracked along the line. In a large quarry such as that at Devine’s Hill, it would often be necessary to assist in the cracking of a block of suitable dimensions, by using wedges inserted across the vertical face of the rock along a horizontal line. The action of a vertical and a horizontal crack would assist the quarryman to produce workable blocks

A row of wedge pits can still be seen in rock at the Devine’s Hill quarry. The rock had wedge pits along the horizontal face and along the vertical face as well. The block so cracked was left and it is not obvious why it was not used. During the conservation work in 1985, a small iron wedge was discovered. Ian Webb (Ref.1) notes that the wedge was 90mm by 40mm. A blacksmith had forged it by folding a strip of 40mm by 10-12mm bar in half. The folded end was forged and flattened to make the taper of the 40 mm wide wedge. Elsewhere, tools such as the head of a stone breaking sledge hammer, a pointed pick head and an iron stone chisel have been found (Ralph Hawkins, Ref.2).

Preparation of Stone Blocks

The large sections of rock at the quarry face were split into blocks of a size appropriate to the need in wall construction and for drain and culvert covers. The same technique for breaking down the large rock sections – creating wedge pits and then carefully splitting the rock to size. For buttressed walls such as those along Devine’s Hill, the blocks were methodically reduced to an accurate size with the chisel end of a pick and then faced with the pointed end by continual picking of the surface. The block was thus reduced to a near rectangular item which would fit neatly in a wall without any grouting between blocks. Ian Webb comments that one large block on Devine’s Hill required 273 pick strokes to complete the facing, a remarkable technique, considering that many of these walls and other structures would not have been seen. This facing technique can be seen in many of the sandstone walls of buildings in Sydney itself and in many beautiful cathedrals and other buildings in Britain.

Dry-laid Walls and Filling for the Great North Road

In developing this section of the story of the Great North Road, great reliance has been placed on the work of Dr Grace Karskens in the Convict Trail Project Monograph Four essays about the Great North Road. The construction of walling along the road over a ten-year period was undertaken by gangs, working under various supervisors. As she emphasises, the resulting retaining walls were built in a wide range of structures from rubble, to block-in-course and fine ashlar masonry work such as we have shown in the design of culvert inlets and outlets. Along a road section, only a single course of stones would be needed to retain a shallow embankment but, in other situations such as on a precipitous slope, over twenty courses of large, well-fitted stone blocks were required to support the road as on Devine’s Hill Ascent.

As Telford and others had stressed, a retaining wall should be battered, i.e. sloped. Such walls were used extensively, especially by Assistant Surveyor Percy Simpson for the major walling undertaken under his direction. Three methods were used to achieve the batter. The first was to incline the beds slightly so that the wall face sloped, with the deviation from horizontal decreasing up to the top coping course so that it was level. The second method was to cut each of the outer stones with a sloped face, especially for larger walls where the thickness of the base had to be considerable. The third method used in the more primitive walls was to recess the superior courses over the inferior ones by some 50 mm, creating a stepped profile. In the crudest of walls no attempt was made to to slope the rough and uneven face at all. Where great attention was given to the structure of the wall as in Devine’s Hill Ascent, it is quite apparent that the stones have tooled faces with evidence of the use of pointed, blunt, broad or flat-edged chisels or gads. Walls of poor quality were roughly worked with a hammer or adze.

Careful field study of the many walls along over a 100 km stretch of the Great North Road led Karskens to adopt a typology, stemming from simple schemes given by 19th century writers Dobson and Tomlinson: their categories were rubble, coursed and ashlar work. The disparate nature of the colonial walls required that each of these categories had to be subdivided according the the standard of dressing, joining and coursing of the walls to provide accurate classification. The first two images are of rubble and rough walls on Finch’s Ascent, with work done under Lt.Jonathon Warner as Assistant Surveyor, classed as Type 1a. Many of walls of these types seem to be few, possibly because they have deteriorated or collapsed. Nevertheless, there are some example which can be seen.

As Telford and others had stressed, a retaining wall should be battered, i.e. sloped. Such walls were used extensively, especially by Assistant Surveyor Percy Simpson for the major walling undertaken under his direction. Three methods were used to achieve the batter. The first was to incline the beds slightly so that the wall face sloped, with the deviation from horizontal decreasing up to the top coping course so that it was level. The second method was to cut each of the outer stones with a sloped face, especially for larger walls where the thickness of the base had to be considerable. The third method used in the more primitive walls was to recess the superior courses over the inferior ones by some 50 mm, creating a stepped profile. In the crudest of walls no attempt was made to to slope the rough and uneven face at all. Where great attention was given to the structure of the wall as in Devine’s Hill Ascent, it is quite apparent that the stones have tooled faces with evidence of the use of pointed, blunt, broad or flat-edged chisels or gads. Walls of poor quality were roughly worked with a hammer or adze.

Careful field study of the many walls along over a 100 km stretch of the Great North Road led Karskens to adopt a typology, stemming from simple schemes given by 19th century writers Dobson and Tomlinson: their categories were rubble, coursed and ashlar work. The disparate nature of the colonial walls required that each of these categories had to be subdivided according the the standard of dressing, joining and coursing of the walls to provide accurate classification. The first two images are of rubble and rough walls on Finch’s Ascent, with work done under Lt.Jonathon Warner as Assistant Surveyor, classed as Type 1a. Many of walls of these types seem to be few, possibly because they have deteriorated or collapsed. Nevertheless, there are some example which can be seen.

Further north of Devine’s Hill and also on a section of road on the south side of the Hawkesbury River at Wiseman’s Ferry, there are walls classed as Type 2a. The stones are roughly squared with a hammer or adze. They are arranged with some attempt at coursing and jointing but this is interrupted by irregularly shaped and sized stones along the length. The result is a wall which is more substantial than a Type 1b wall. Type 2b walls have better prepared stones allowing rough jointing and more definite courses. The stone sometimes have tooled faces.

In comparison, Type 3b walls have the stones dressed to definite dimensions to give a smooth face and tight bedding with perpendicular joints and even horizontal coursing. We have already shown examples of this fine ashlar work in the huge walls with their heavy buttressing on Devine’s Hill. The detailed ashlar masonary is evident in the V-shaped ends of the Clare’s Bridge central pylon. There are gracefully curved retaining walls at Mt McQuoid and Devine’s Hill. We can only give a couple of examples here.

What was to become clear from the study was that the Assistant Surveyor’s attitude and competence were primary influences, the supervisory capabilities of their subordinate overseers was vital to good results and the skills of the members of the road gangs were very important. It became important to look at the record of each gang’s work when read in conjunction with the Weekly and Monthly Road Gang Reports on each gang’s progress, its movements, its skills and composition. The details of this investigation would have to be read in Karskens’ Convict Trail Project Monograph but you can go to the next menu item where an outline of her solution to some extraordinary anomalies in the masonry styles.

Masonry Style Anomalies

In the item about Great North Road Walls and Filling, attention was drawn to the investigations which were carried out by Grace Karskens in attempting to discern the broad pattern in the range of masonry styles and their distribution along the road, taking into account the standards of the various Assistant Surveyors mentioned in their Weekly and Monthly reports. Jonathon Warner stressed the quick, economical and consequently rough road building with walls not more than four feet high (Type 1b) and even boasted about it. The result was crude stonework quality. This was in striking contrast to the lofty and massive side walls (Type 3a) described by Percy Simpson up the same slope that had been mentioned by Warner. Simpson’s new ascent up Devine’s Hill has walls almost all of quality Type 3a or 3b. Yet there is a major anomaly in this explanation. How was it that, under Simpson’s ambitious supervision, there is work at the top of Devine’s Hill that is of the poorest quality found on the road (Type 1a) when only a few hundred metres down the road to the south there is all that fine ashlar work?

Karkens found the solution to the anomaly in a comparison of the written and material records. By juxtaposing the location of different styles of surviving stonework with the known distribution of Road Gangs between 1827 and 1832, she found that a pattern of association between certain gangs and particular styles emerged. Only a brief summary of what she found can be given here.

• Nos. 1 & 4 Gangs remained during the whole period on the rugged area approaching the Hawkesbury, both sides at Wiseman’s Ferry – high quality work of Type 3a and 3b.

• No. 8 Iron Gang consistently stationed in areas which today feature only poor quality work – Maroota, section of Devine’s Hill to Ten Mile Hollow, vicinity of Hungry Flat and Sampson’s Pass (mostly Type 1a or 1b).

• No. 9 Iron Gang built the fine retaining wall in the Little Maroota Forest area (Type 3a), the ascent of Mt Baxter (Type 2b) and the stone ramp at Mt Manning (Type 3a).

The Gangs appear to have been organised according to skills.The least skilled and unskilled were placed in No. 8 Iron Gang and assigned the construction of large stretches of road where no difficult sections occurred. Men with more skills were placed in No.4 and No. 9 Iron Gangs. The best masons available were recruited into No. 3 Iron Gang and No. 25 Road Party. Karskens points out that the latter Party was the gang that put up rough rubble walls (Type 1b) on Warner’s first zig-zag ascent north of the Hawkesbury in 1828 but, under Simpson’s direction in the next two years, they constructed the remarkable walls of Devine’s Hill ascent. She believes that the poor workmen were either replaced by more skilled men after Simpson’s arrival, or they were somehow persuaded to attain skills in stone masonry and encouraged to practise and perfect them.

The Assistant Surveryors, who were interested in constructing durable and impressive road such as Simpson and Finch, evidently spent some time instructing their overseers in various methods of road building. The acquisition of such useful skills as rock blasting, stone masonry, embanking and draining (apparently in great demand in the colony and thus potentially valuable in the future), was an incentive for the overseers to keep the men at work and to maintain high standards. The consistency of style and design for walls and drainage structures could not have been produced by gangs with men being changed from week to week and month to month. The answer lay in the proportion of skilled to unskilled men, as derived by Karskens from the numerous Road Gang Reports. They show that the number of men actually employed in the skilled work mentioned above was relatively small, ranging between two and ten men out of a gang of about fifty. The rest were employed on tasks which required little or no skills – clearing the line of trees, cutting through earth and rock, filling embankments and breaking and carting stone. It is likely that runaways came from this group, while the men employed in the more challenging and interesting skilled work chose to remain on the job.

Karskens comments The walls they built thus reveal overlaid evidence of their remarkable perseverance and skills, the the diligent supervision of the overseers, and of the ambitious visions of the Assistant Surveyors.

Karkens found the solution to the anomaly in a comparison of the written and material records. By juxtaposing the location of different styles of surviving stonework with the known distribution of Road Gangs between 1827 and 1832, she found that a pattern of association between certain gangs and particular styles emerged. Only a brief summary of what she found can be given here.

• Nos. 1 & 4 Gangs remained during the whole period on the rugged area approaching the Hawkesbury, both sides at Wiseman’s Ferry – high quality work of Type 3a and 3b.

• No. 8 Iron Gang consistently stationed in areas which today feature only poor quality work – Maroota, section of Devine’s Hill to Ten Mile Hollow, vicinity of Hungry Flat and Sampson’s Pass (mostly Type 1a or 1b).

• No. 9 Iron Gang built the fine retaining wall in the Little Maroota Forest area (Type 3a), the ascent of Mt Baxter (Type 2b) and the stone ramp at Mt Manning (Type 3a).

The Gangs appear to have been organised according to skills.The least skilled and unskilled were placed in No. 8 Iron Gang and assigned the construction of large stretches of road where no difficult sections occurred. Men with more skills were placed in No.4 and No. 9 Iron Gangs. The best masons available were recruited into No. 3 Iron Gang and No. 25 Road Party. Karskens points out that the latter Party was the gang that put up rough rubble walls (Type 1b) on Warner’s first zig-zag ascent north of the Hawkesbury in 1828 but, under Simpson’s direction in the next two years, they constructed the remarkable walls of Devine’s Hill ascent. She believes that the poor workmen were either replaced by more skilled men after Simpson’s arrival, or they were somehow persuaded to attain skills in stone masonry and encouraged to practise and perfect them.

The Assistant Surveryors, who were interested in constructing durable and impressive road such as Simpson and Finch, evidently spent some time instructing their overseers in various methods of road building. The acquisition of such useful skills as rock blasting, stone masonry, embanking and draining (apparently in great demand in the colony and thus potentially valuable in the future), was an incentive for the overseers to keep the men at work and to maintain high standards. The consistency of style and design for walls and drainage structures could not have been produced by gangs with men being changed from week to week and month to month. The answer lay in the proportion of skilled to unskilled men, as derived by Karskens from the numerous Road Gang Reports. They show that the number of men actually employed in the skilled work mentioned above was relatively small, ranging between two and ten men out of a gang of about fifty. The rest were employed on tasks which required little or no skills – clearing the line of trees, cutting through earth and rock, filling embankments and breaking and carting stone. It is likely that runaways came from this group, while the men employed in the more challenging and interesting skilled work chose to remain on the job.

Karskens comments The walls they built thus reveal overlaid evidence of their remarkable perseverance and skills, the the diligent supervision of the overseers, and of the ambitious visions of the Assistant Surveyors.

Comparison of Distributions

Stonework Types versus Convict Gangs & Parties

Distribution of Great North Road stonework types, 1983. The best quality work occurs mainly around Wiseman’s Ferry and at Mt McQuoid and Mt Simpson, while the walls of poorer quality are scattered along the road between Wiseman’s Ferry and Mt Manning. Between Mt Baxter and Hungry Flat, the originally poor quality work has disintegrated or occurs only as small intermittent fragments which do not merit inclusion on this map.