Convict Medical Care

In construction operations of the size of the development of the Great North Road, sickness and ill-health would have been prevalent but there were other reasons for the assistant surveyors and their assistants to ensure that some form of medical attention was available. It might have been primitive by our present day standards.

Trevor Patrick of the Dural & District Historical Society investigated this aspect of the medical care of convicts. As a pharmacist, he was in a position to understand the material that was available through the various records and writings of the day. One rich source of information was the literature of Surgeon John Harris after whom the suburb of Harris Park is named. Harris came to Sydney with the Second Fleet as a member of the 102nd Regiment. The text books he used for knowledge of treatments are on display at his home, Experimental Farm in Ruse Street at Harris Park.

Surgeons were require to attend to all the inhabitants of the colony, convict or free settler. Hospitals were established in Sydney, Parramatta and Windsor when the plots of land were laid out for townships. John Harris followed Surgeon Thomas Arndell in becoming head of the Parramatta Hospital on Arndell’s retirement.

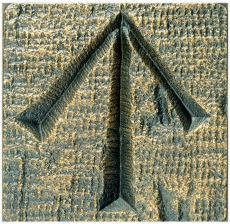

Medical care along the track which became the Great North Road was provided by an assistant to the Assistant Surveyor of the section of the road. He had a medical chest which was replenished from time to time by submission of a requisition. Details of one such requisition from a surveyor at Lower Portland Head (Wiseman’s Ferry) is listed in Trevor Patrick’s article, together with a picture of a medical chest on display at Experimental Farm. The medical chest there has a wide range of contents, 25 of which are listed in the article, together with a most interesting explanation of what each item was and its uses. The chest also contained a number of rubber catheters and would have also held a variety of surgical needles and thread [catgut, tough cord made from intestines, usually sheep] for sewing up wounds.

Trevor Patrick of the Dural & District Historical Society investigated this aspect of the medical care of convicts. As a pharmacist, he was in a position to understand the material that was available through the various records and writings of the day. One rich source of information was the literature of Surgeon John Harris after whom the suburb of Harris Park is named. Harris came to Sydney with the Second Fleet as a member of the 102nd Regiment. The text books he used for knowledge of treatments are on display at his home, Experimental Farm in Ruse Street at Harris Park.

Surgeons were require to attend to all the inhabitants of the colony, convict or free settler. Hospitals were established in Sydney, Parramatta and Windsor when the plots of land were laid out for townships. John Harris followed Surgeon Thomas Arndell in becoming head of the Parramatta Hospital on Arndell’s retirement.

Medical care along the track which became the Great North Road was provided by an assistant to the Assistant Surveyor of the section of the road. He had a medical chest which was replenished from time to time by submission of a requisition. Details of one such requisition from a surveyor at Lower Portland Head (Wiseman’s Ferry) is listed in Trevor Patrick’s article, together with a picture of a medical chest on display at Experimental Farm. The medical chest there has a wide range of contents, 25 of which are listed in the article, together with a most interesting explanation of what each item was and its uses. The chest also contained a number of rubber catheters and would have also held a variety of surgical needles and thread [catgut, tough cord made from intestines, usually sheep] for sewing up wounds.

Requisition for the undermentioned articles for use of the Service at Lower Portland Head Sept 17th 1827

Trevor Patrick explains the use of items requisitioned for the medical chest:

The simple ointment was used as a soothing balm for dry, chafed and cracked skin. This would be a common skin condition with the men working out-of-doors and moving logs and stone to clear and build the road. Aperient pills moved the bowels and indicate the low fibre content of the diet and the common belief that the bowels must be kept active every day. Calomel is a mercurous compound that also acts as a purgative [forces the bowel to open].

Adhesive plaster and fine lint were used to cover wounds which most certainly happened in the environment of axes and saws used in cutting down trees, and of wedges, mauls, hammers and gunpowder used in splitting rock. The costic (sic), [caustic], was used as an antiseptic in weak concentrations and to remove proud flesh [dead tissue] from wounds.

Part of the need for aperients seems have been that the rations for the convicts were plain and often fell below the required amount, attributable to the unreliability of the private suppliers which has been mentioned elsewhere in these pages. Tobacco was forbidden, no milk was issued, and maize meal was substituted for part of the wheat issue. At night, convicts were locked in huts constructed at strategic sites along the road.

Two aspects of medical treatment are mentioned in the article. In every Iron Gang, there was a man known as the Scourger. His duty was to apply the whip to those convicts who had disobeyed lawful instructions. The medical kit would have been used after these punishments to ensure the convict did not become a burden to the road gang.

Injuries did occur during the construction of the road from Parramatta River to the Hunter Valley, as might be expected with the operations which had to be used. Correspondence in 1829 [NSW Archives N29/133] shows men had been seriously injured, to such an extent that a boat was hired from a local farmer to take them from the Wiseman’s Ferry area up the Hawkesbury River to Windsor Hospital.

Colonial Secretary’s Office Sydney 26th October 1829 N29/133

Sir,

I have the honour to acknowledge the receipt of your letter of the 12th instant enclosing an account amounting to three pounds five shillings for the hire of a Boat from James Molloy a settler in the district of Lower Portland Head, for the purpose of conveying Prisoners from the iron Gangs in that neighbourhood to the Hospital at Windsor a distance of thirty-five miles.

In reply I am directed by the Governor to inform you, that as it appears from the report of Mr Assistant Surveyor Simpson that the men so removed were unable to travel to the Hospital, to which it was necessary to send them, and that no other equally convenient conveyance could be procured, His Excellency approved of your including the above sum in your contingent abstract as requested, the before mentioned account which is herewith returned to you. A certificate that the sum charged is reasonable and that the expense has been necessarily incurred Ñ the receipt of the payee and this letter being produced as voucher for the payment.

Edmund Lockyer Esq

Surveyor of Roads & Bridges

£3/5/0

Signed F.C. Harrington

The Convict Medical Care article gives attention to John Harris as a rather wonderful man whose medical knowledge helped many. Harris showed his surgical skills by successfully attending Captain Arthur Phillip who was speared in 1790 by an aborigine on the beach we now call Manly. He also accompanied Surveyor-General John Oxley during the exploration to find new farming land in 1818. William Blake of this group was speared in two places during an attack by natives who wanted Blake’s axe. Oxley did not think that Blake would recover from his wounds after Harris extracted both spears. The skill of John Harris was nevertheless sufficent for Blake to recover. The article contains much more interesting backgound about this man and the circumstances of his life in the colony.

Reference:

“Convict Medical Care … in the colony of New South Wales” by Trevor Patrick; “The Doorals”, Journal of the Dural & District Historical Society Inc., Vol III, 1997

The simple ointment was used as a soothing balm for dry, chafed and cracked skin. This would be a common skin condition with the men working out-of-doors and moving logs and stone to clear and build the road. Aperient pills moved the bowels and indicate the low fibre content of the diet and the common belief that the bowels must be kept active every day. Calomel is a mercurous compound that also acts as a purgative [forces the bowel to open].

Adhesive plaster and fine lint were used to cover wounds which most certainly happened in the environment of axes and saws used in cutting down trees, and of wedges, mauls, hammers and gunpowder used in splitting rock. The costic (sic), [caustic], was used as an antiseptic in weak concentrations and to remove proud flesh [dead tissue] from wounds.

Part of the need for aperients seems have been that the rations for the convicts were plain and often fell below the required amount, attributable to the unreliability of the private suppliers which has been mentioned elsewhere in these pages. Tobacco was forbidden, no milk was issued, and maize meal was substituted for part of the wheat issue. At night, convicts were locked in huts constructed at strategic sites along the road.

Two aspects of medical treatment are mentioned in the article. In every Iron Gang, there was a man known as the Scourger. His duty was to apply the whip to those convicts who had disobeyed lawful instructions. The medical kit would have been used after these punishments to ensure the convict did not become a burden to the road gang.

Injuries did occur during the construction of the road from Parramatta River to the Hunter Valley, as might be expected with the operations which had to be used. Correspondence in 1829 [NSW Archives N29/133] shows men had been seriously injured, to such an extent that a boat was hired from a local farmer to take them from the Wiseman’s Ferry area up the Hawkesbury River to Windsor Hospital.

Colonial Secretary’s Office Sydney 26th October 1829 N29/133

Sir,

I have the honour to acknowledge the receipt of your letter of the 12th instant enclosing an account amounting to three pounds five shillings for the hire of a Boat from James Molloy a settler in the district of Lower Portland Head, for the purpose of conveying Prisoners from the iron Gangs in that neighbourhood to the Hospital at Windsor a distance of thirty-five miles.

In reply I am directed by the Governor to inform you, that as it appears from the report of Mr Assistant Surveyor Simpson that the men so removed were unable to travel to the Hospital, to which it was necessary to send them, and that no other equally convenient conveyance could be procured, His Excellency approved of your including the above sum in your contingent abstract as requested, the before mentioned account which is herewith returned to you. A certificate that the sum charged is reasonable and that the expense has been necessarily incurred Ñ the receipt of the payee and this letter being produced as voucher for the payment.

Edmund Lockyer Esq

Surveyor of Roads & Bridges

£3/5/0

Signed F.C. Harrington

The Convict Medical Care article gives attention to John Harris as a rather wonderful man whose medical knowledge helped many. Harris showed his surgical skills by successfully attending Captain Arthur Phillip who was speared in 1790 by an aborigine on the beach we now call Manly. He also accompanied Surveyor-General John Oxley during the exploration to find new farming land in 1818. William Blake of this group was speared in two places during an attack by natives who wanted Blake’s axe. Oxley did not think that Blake would recover from his wounds after Harris extracted both spears. The skill of John Harris was nevertheless sufficent for Blake to recover. The article contains much more interesting backgound about this man and the circumstances of his life in the colony.

Reference:

“Convict Medical Care … in the colony of New South Wales” by Trevor Patrick; “The Doorals”, Journal of the Dural & District Historical Society Inc., Vol III, 1997

Convict Dispensaries & Hospitals on the Great North Road

In the article by Trevor Patrick, mention was made of an assistant to the Assistant Surveyor who used the materials in the medical chest to treat convicts who had been injured in some way. At this early stage of the preparation of information about the medical treatment of convicts on the Great North Road construction, it is interesting to note a comment made by Dr Grace Karskens when she was being interviewed and filmed for a video by Claude and Bronwyn Aliotti, The Convict Trail.

This comment is in By Force of Maul & Wedge, compiled by Bill Bottomley. Bronwyn had asked, “Were there many lives lost while they were building the Road?” Here is the reply:

It’s not all that overt in the records, although there is some reference to Simpson wanting a doctor or some sort of First Aid provided because he said that the men “were liable to be hurt in the work that they do.” You know, working with gunpowder and bullocks and heavy rocks in very steep locations would have been very dangerous.

In the Bottomley compilation, Ken Marheine was interviewed. He commented on the letter from the Colonial Secretary to Surveyor Lockyer on the transportation of injured convicts by boat in 1829 to Windsor Hospital. He went on to remark that the Assistant Surveyors had their first aid spot on each site and that they did look after their convict gangs.

“I’d like to quote from a letter written by Heneage Finch on September 25th 1830. It is to the Surveyor-General: I have the honour to inform you that the Overseer of the Bridge Party under my orders expects to have completed the work which he now has in hand, which is building a dispensary etc. for the medical attendant attached to these gangs, by the end of the next week, and that I have another week to employ thereupon. … and even at Wollombi there’s one place there where they had a hospital – it’s still known as Hospital Hill. So they did look after them.”

In the Convict Trail Project Monograph “Four Essays about the Great North Road”, Dr Karskens has one essay on The Convict Road Station Site at Wiseman’s Ferry. Governors Darling and Bourke issued instructions about the design and guarding of the the prisoners at this stockade by military detachment. Bourke’s instructions were increasingly detailed with reference to the placement of huts, guard houses, barracks and so on. Apart from the numerous buildings referred to in these instructions, there is mention of huts to be used as a hospital and as a dispensary for the medical attendant.

Ian Webb, in his book Blood Sweat and Irons pp21-25, outlines the detailed instructions which were transmitted to Surveyor General Mitchell from the Colonial Secretary and signed by the Governor R. Darling. In these instructions, one paragraph is interesting in the medical context:

An Assistant Surgeon will be employed with the detachment and will have the medical charge of the gangs working in the neighbourhood. A hut must be fitted up for the treatment of slight cases – Should any serious ones occur, the man must be sent to the hospital at Windsor.

Ian Webb notes that sick or seriously injured convicts from the gangs were transported to the hospital at Windsor. During 1829, this was done by using a hired boat manned by a member of the No. 25 Road Party. The re-hiring of this boat in October 1829 has already been mentioned. Minor injuries and complaints were handled by an assistant surgeon who worked in a hut specially built as a hospital and dispensary. He also visited the gangs stationed away from the stockades to administer medicines and treat the minor injuries.

Just who were these medical attendants? We have one mention of an attendant by Ian Webb. In May 1830, a member of the No. 25 Road Party, Jasper Walton (Countess of Harcourt), was listed as the assistant surgeon for the area [Ref: Road Gang Reports, 1827-1830, AONSW reel 590]. It will be most interesting to find out in more detail how such men, whether Road Gang or Ticket of Leave convicts or free-by-servitude men, had been or were trained in the medical treatment of their fellows.

By April 1832, with the road works in the Wisemans District nearly completed, Simpson reported:

That in all serious cases requiring convicts being sent to the nearest General Hospital for medical treatment, they should be conveyed in a covered cart, locked up and escorted by a file of the stockade guard aided by an Assistant Overseer armed with a cutlass. For slight cases requiring attendance at the local dispensary, they should be escorted handcuffed on a chain by a file of the guard and an Assistant Overseer, armed as before. [Ref: Simpson to Mitchell, Apr. 1832, Box 2/1579.2]

As Darling and Bourke instructed, these men, no matter how sick or injured, were to be prevented from escaping legal custody.

This comment is in By Force of Maul & Wedge, compiled by Bill Bottomley. Bronwyn had asked, “Were there many lives lost while they were building the Road?” Here is the reply:

It’s not all that overt in the records, although there is some reference to Simpson wanting a doctor or some sort of First Aid provided because he said that the men “were liable to be hurt in the work that they do.” You know, working with gunpowder and bullocks and heavy rocks in very steep locations would have been very dangerous.

In the Bottomley compilation, Ken Marheine was interviewed. He commented on the letter from the Colonial Secretary to Surveyor Lockyer on the transportation of injured convicts by boat in 1829 to Windsor Hospital. He went on to remark that the Assistant Surveyors had their first aid spot on each site and that they did look after their convict gangs.

“I’d like to quote from a letter written by Heneage Finch on September 25th 1830. It is to the Surveyor-General: I have the honour to inform you that the Overseer of the Bridge Party under my orders expects to have completed the work which he now has in hand, which is building a dispensary etc. for the medical attendant attached to these gangs, by the end of the next week, and that I have another week to employ thereupon. … and even at Wollombi there’s one place there where they had a hospital – it’s still known as Hospital Hill. So they did look after them.”

In the Convict Trail Project Monograph “Four Essays about the Great North Road”, Dr Karskens has one essay on The Convict Road Station Site at Wiseman’s Ferry. Governors Darling and Bourke issued instructions about the design and guarding of the the prisoners at this stockade by military detachment. Bourke’s instructions were increasingly detailed with reference to the placement of huts, guard houses, barracks and so on. Apart from the numerous buildings referred to in these instructions, there is mention of huts to be used as a hospital and as a dispensary for the medical attendant.

Ian Webb, in his book Blood Sweat and Irons pp21-25, outlines the detailed instructions which were transmitted to Surveyor General Mitchell from the Colonial Secretary and signed by the Governor R. Darling. In these instructions, one paragraph is interesting in the medical context:

An Assistant Surgeon will be employed with the detachment and will have the medical charge of the gangs working in the neighbourhood. A hut must be fitted up for the treatment of slight cases – Should any serious ones occur, the man must be sent to the hospital at Windsor.

Ian Webb notes that sick or seriously injured convicts from the gangs were transported to the hospital at Windsor. During 1829, this was done by using a hired boat manned by a member of the No. 25 Road Party. The re-hiring of this boat in October 1829 has already been mentioned. Minor injuries and complaints were handled by an assistant surgeon who worked in a hut specially built as a hospital and dispensary. He also visited the gangs stationed away from the stockades to administer medicines and treat the minor injuries.

Just who were these medical attendants? We have one mention of an attendant by Ian Webb. In May 1830, a member of the No. 25 Road Party, Jasper Walton (Countess of Harcourt), was listed as the assistant surgeon for the area [Ref: Road Gang Reports, 1827-1830, AONSW reel 590]. It will be most interesting to find out in more detail how such men, whether Road Gang or Ticket of Leave convicts or free-by-servitude men, had been or were trained in the medical treatment of their fellows.

By April 1832, with the road works in the Wisemans District nearly completed, Simpson reported:

That in all serious cases requiring convicts being sent to the nearest General Hospital for medical treatment, they should be conveyed in a covered cart, locked up and escorted by a file of the stockade guard aided by an Assistant Overseer armed with a cutlass. For slight cases requiring attendance at the local dispensary, they should be escorted handcuffed on a chain by a file of the guard and an Assistant Overseer, armed as before. [Ref: Simpson to Mitchell, Apr. 1832, Box 2/1579.2]

As Darling and Bourke instructed, these men, no matter how sick or injured, were to be prevented from escaping legal custody.